Quote of the week

“Beware the barrenness of a busy life.”

- Socrates

Edition 51 - December 21, 2025

“Beware the barrenness of a busy life.”

- Socrates

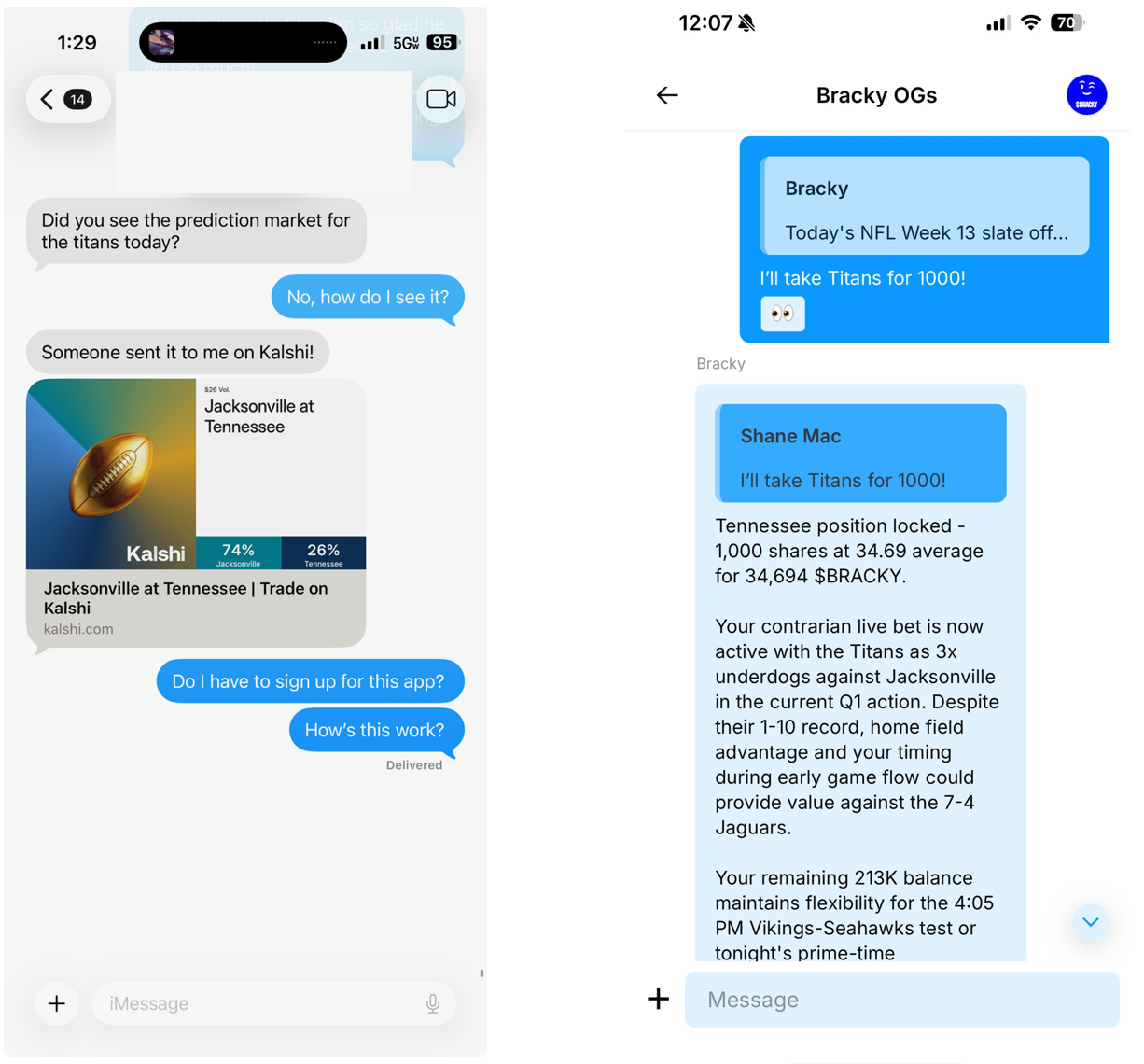

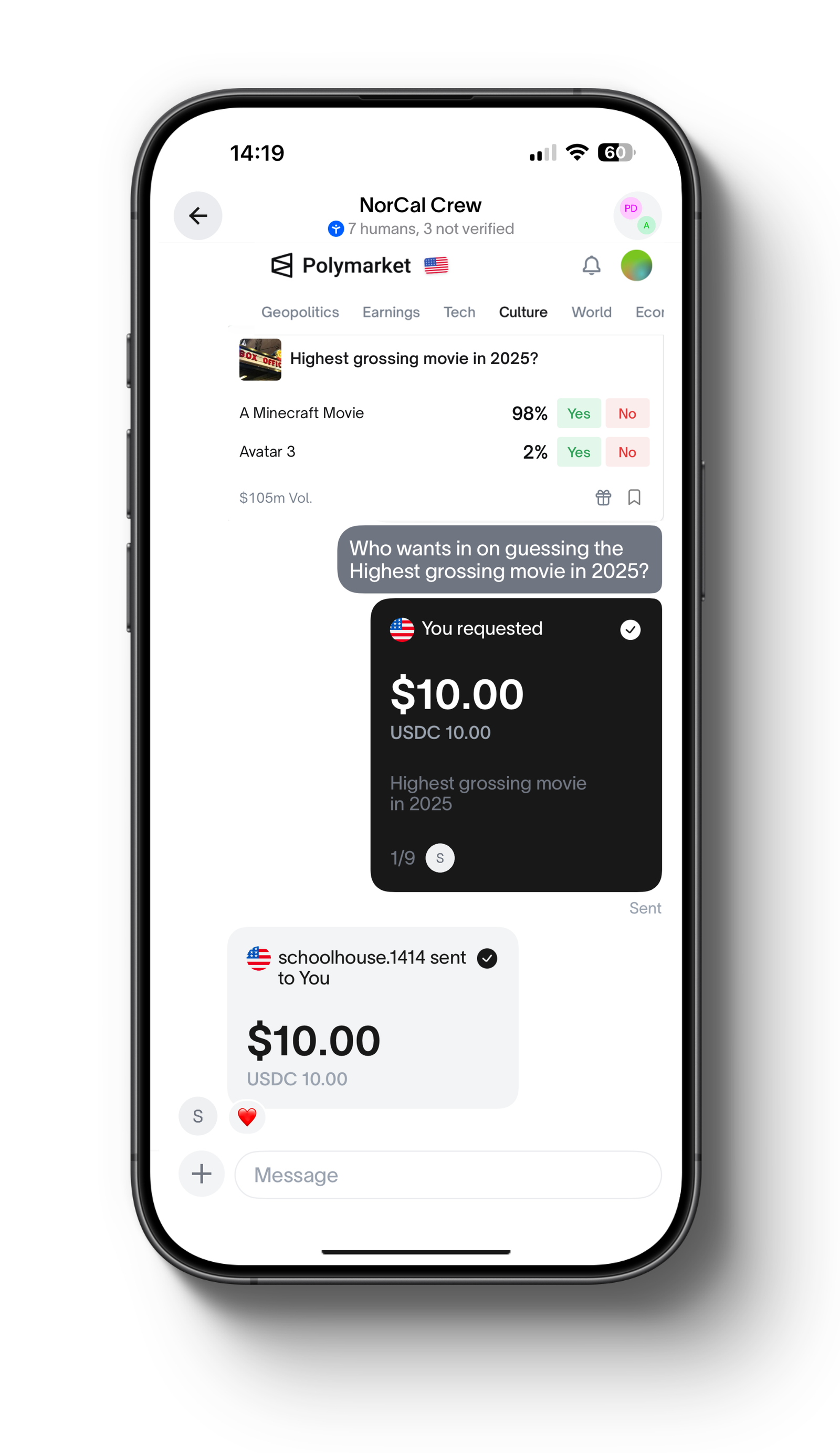

I recently read this article where the author argues that the future of prediction markets is less about building better standalone apps and more about meeting people where they already talk. The core idea is simple. Predictions are social by nature. People float takes, make informal bets, and pressure test ideas inside group chats long before they ever open a dedicated platform. Prediction markets struggle not because the incentives are wrong, but because the interface is in the wrong place. The next leap forward likely comes from embedding betting mechanics directly into existing communication flows.

That framing resonated with me because it mirrors how I like to engage in low stakes sports gambling from time to time, especially with friends. To be clear, this is legal where I live and I treat it as entertainment, not income. Most of the fun is not the bet itself, but the shared experience. Talking trash. Negotiating picks. Watching the games together. Recently one of the major sportsbooks rolled out a co op parlay builder where each person in a group can choose a leg of the parlay, and then everyone can opt in and bet with their own funds. On paper, it feels like the perfect product. Collaborative, social, lightweight.

In practice, it falls flat. The bets never make it out of the group chat. Someone posts a link. Someone else forgets. Another person gets stuck logging in. There are too many clicks and too much friction for something that is supposed to feel casual and fun. So what can and will sportsbooks and other betting applications do? In my eyes, there are three options: 1) do nothing 2) try to build social directly in their apps 3) work together on some kind of open source framework for making their software directly available from major communication forums like iMessage, WhatsApp, and Discord through partnerships, strong engineering, and intense lobbying.

Option 2 is what most of these apps will do, or are already doing (Think Robinhood). Option 3 feels ideal for the consumer but probably impractical in reality given platform politics, regulation, and misaligned incentives. My guess is we land in a messy middle. Slightly more social features inside apps, slightly better sharing outside of them, and very little that feels truly native to the places people already spend their time. The gravity of group chats is real, but bending large institutions toward it takes time. We'll see.

A social license is not a legal document or a regulatory checkbox. It is something societies collectively grant when an activity is disruptive or destructive in the short term but delivers lasting benefits along the way. The damage from said activity can be real, so can the fear. What makes a social license possible is visible value. People tolerate disruption when they can clearly see what they are getting in return, not someday, but as the change is happening.

History offers clear examples of how this works. The railroads reshaped landscapes, displaced communities, and concentrated power, yet they were broadly tolerated because they connected markets and lowered the cost of goods. Importantly, some of the wealth created along the way was returned to the public. Andrew Carnegie funded more than 2,500 public libraries across the United States and beyond, explicitly tying industrial wealth to social improvement. Electrification followed a similar pattern. Power plants were intrusive, dangerous, and unpopular, but the payoff was lighting, refrigeration, and modern industry. The disruption was balanced by tangible, shared upside.

That balance is missing today in the AI economy. The largest AI companies are creating enormous value, but very little of it is directly visible to everyday consumers. Instead, people hear about water usage, job loss, and massive data centers drawing power from already strained grids. Some of these fears are overstated, some are justified, and almost all are poorly explained. This is where a social license must be earned, not assumed. These companies have the balance sheets to do it. They should build the energy infrastructure their data centers require, then build twice as much. Solar, nuclear, geothermal, and other clean sources should power the facilities, with the excess electricity returned to the grid and delivered to nearby cities and towns.

The payoff would be immediate and measurable. More generation means lower electric rates and a more resilient power system. Cheap, abundant energy reduces the cost of manufacturing, housing, transportation, and computing itself. It creates room for experimentation and accelerates innovation across the economy. China is demonstrating this dynamic in real time, using massive energy investment to drive down costs and scale new industries. If AI is going to reshape society, it needs a social license to do so. The fastest way to earn it is simple. Give people more power, literally, than you take.

A provocative idea has escaped the realm of sci fi and landed in boardrooms: what if the next generation of AI data centers belongs in space? In the past year, the concept of orbital compute has been floated by the heads of major American tech companies as a potential path around Earth’s growing infrastructure bottlenecks. The pitch is straightforward. Put servers in orbit, power them with near constant sunlight, cool them by radiating heat into the vacuum, and sidestep the messy constraints of land, water, and local permitting. The backlash has been just as loud. Critics point to brutal launch economics, hard engineering realities, and the simple fact that data centers on Earth are already an optimized machine.

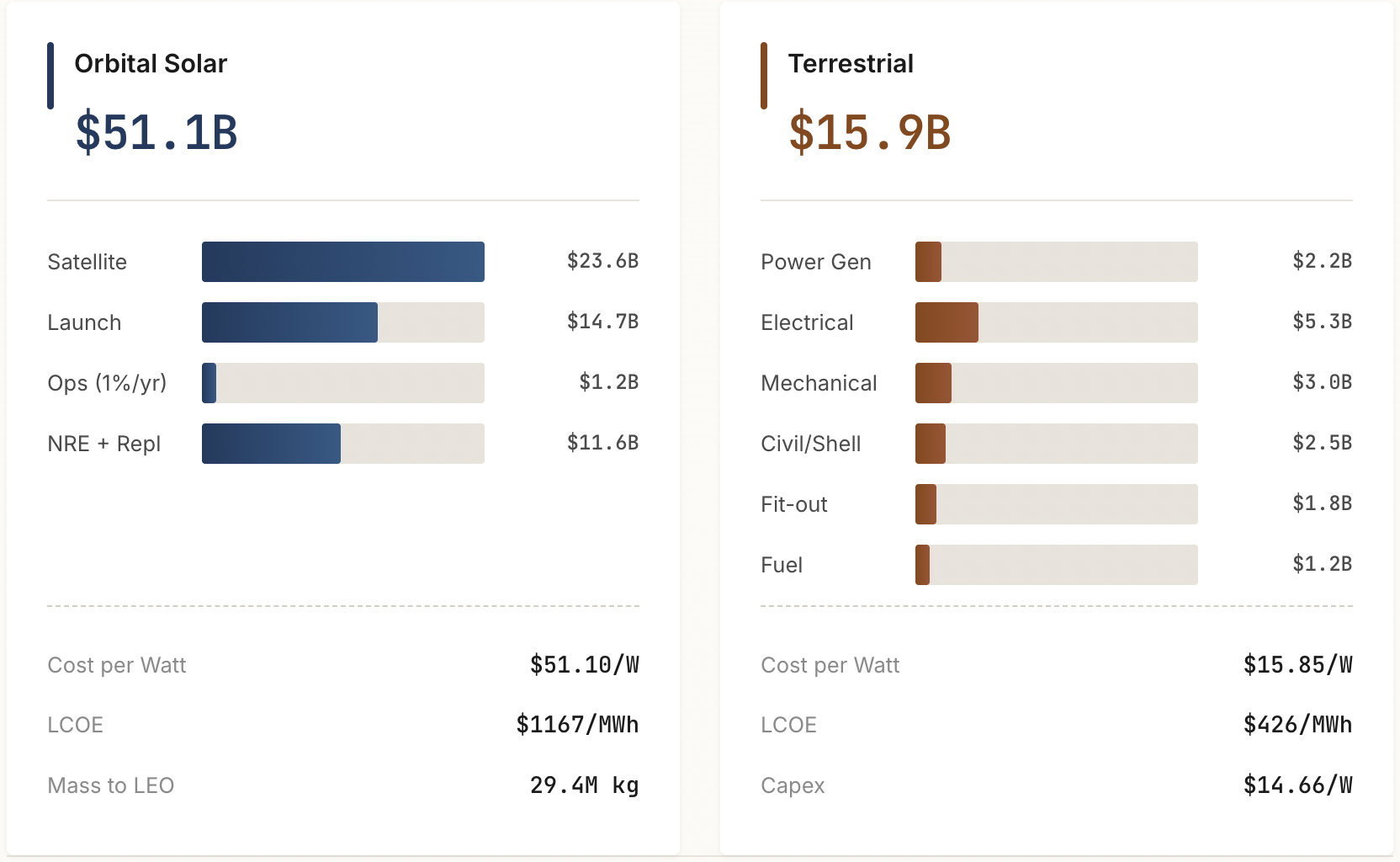

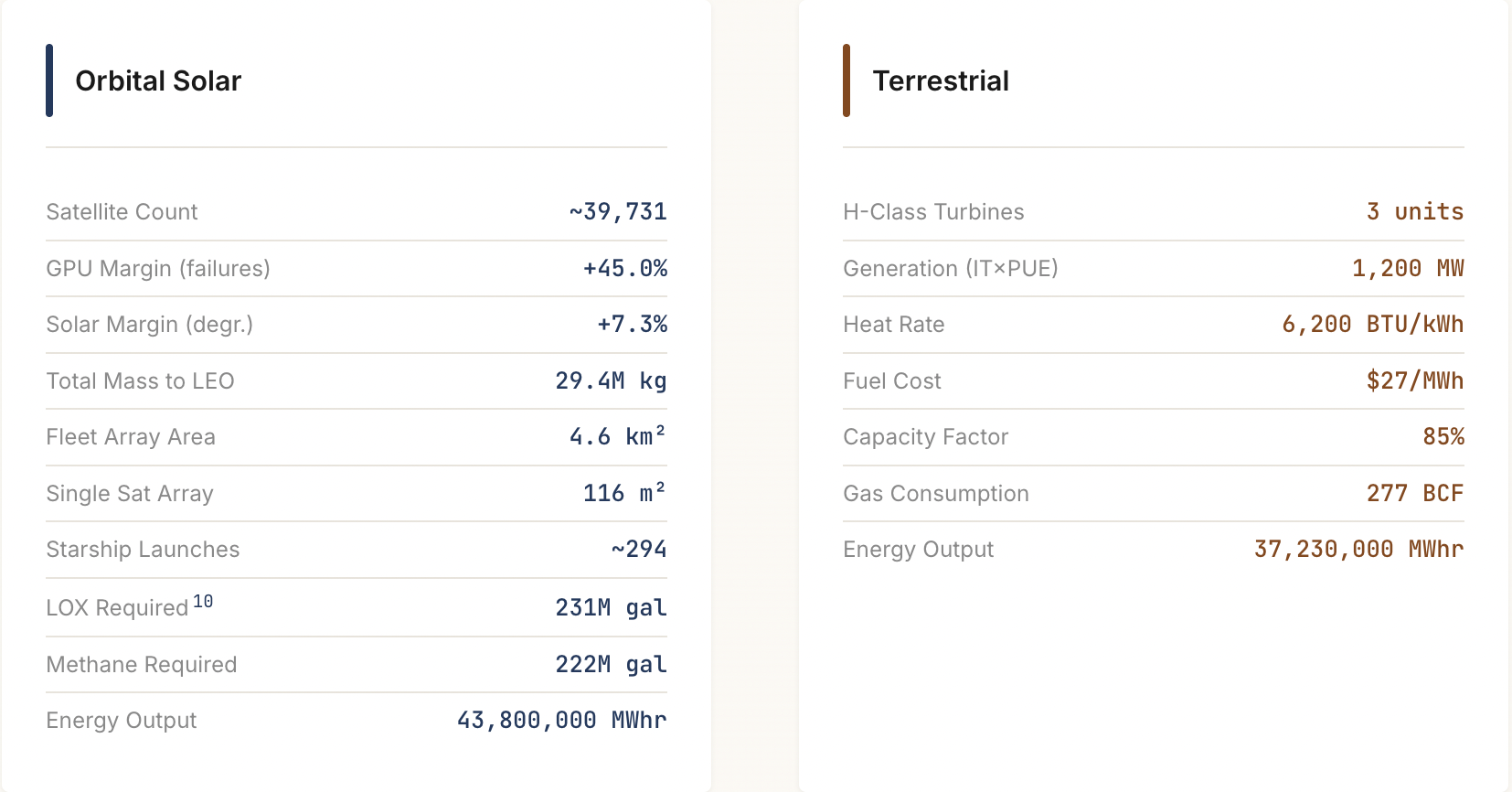

One of the clearest treatments of the idea comes from Andrew McCalip, who approaches the question with a refreshing lack of romance. His core move is to step back from the futuristic visuals and ask what actually matters: is a watt of compute in orbit cheaper, better, or more valuable than a watt on the ground? Much of the public conversation skips this step, racing toward timelines and prototypes without doing the basic arithmetic. McCalip builds a cost model that treats usable power as the fundamental unit, then layers in the unavoidable ingredients of an orbital system: launch costs, spacecraft hardware, operations, and replacement cycles.

The conclusion is not that space data centers are impossible. It is that the economics are currently unforgiving. Under reasonable baseline assumptions, the cost per watt of orbital power and compute comes out far higher than terrestrial alternatives, even before accounting for the extra complications space demands, like radiation tolerance, limited servicing options, and reliability over long durations. The physics offers real advantages, especially abundant solar energy and radiative cooling. But those advantages only matter if they can be captured at a cost that competes with Earth’s steadily improving data center stack.

McCalip’s most useful contribution is the frame, not a dramatic yes or no. If proponents want orbital compute to be more than a headline, they need to name the economic thresholds that would make it rational, then explain what changes could realistically hit them. That means sharper targets for launch costs, manufacturing scale, and system lifetimes, plus a clear story for how the data actually gets to and from orbit without turning bandwidth into the hidden tax. Until the numbers close, “servers in the sky” is best understood as a pressure valve for a real problem on Earth: AI is pushing infrastructure to the limit, and people are searching for new surfaces to stand on.

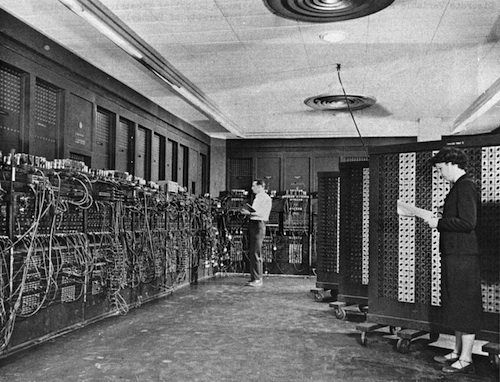

This is the story of computing before operating systems existed. Early computers did not have a central layer to manage hardware, memory, or programs. Software ran directly on the machine, with each program responsible for controlling everything it touched. That approach worked when systems were simple and users were experts, but it made computing fragile and difficult to scale. Without an OS, every machine felt unique and every mistake was costly.

Because there was no shared system layer, each program had to solve the same foundational problems from scratch. Loading code, handling input, managing resources, and recovering from errors all lived inside the application itself. That made programs large, tightly coupled to hardware, and hard to reuse. Improvements rarely transferred cleanly between machines. Progress existed, but it moved in isolated pockets instead of compounding across the ecosystem.

The operating system emerged as a response to this growing complexity. It centralized responsibility for the hardest problems and created a stable platform for everything above it. Once that layer existed, software could focus on purpose instead of survival. This shift unlocked scale, collaboration, and the layered design that defines modern computing. What feels like a basic requirement today was once the missing piece that made everything else possible.

A new long-term study suggests that regularly eating high-fat cheeses and cream may be linked with a lower risk of dementia: people who consumed about 50 g of high-fat cheese a day had a roughly 13 % reduced risk of developing dementia and a notably lower risk of vascular dementia, and those eating about 20 g of high-fat cream daily also showed a reduced risk, while low-fat dairy didn’t show the same association; researchers say this points to a potential protective link but isn’t proof that these foods directly prevent the disease and more research is needed.

A community-led effort in Toronto has turned a rubbish-clogged water basin by the lake into a revitalized, cleaner natural space, showing how sustained cleanup and environmental care can transform polluted urban shores into healthier, more attractive areas for people and wildlife.

A series of quiet but meaningful wins around the world point to real progress: the ozone layer continues to recover, with the Antarctic ozone hole closing earlier than in recent years, while an Ebola outbreak in the Congo has been officially declared over after a successful vaccination campaign. At the same time, practical innovations are improving lives, from safer sound technology for electric cars to new banking access for people without fixed addresses, alongside scientific breakthroughs that could reshape medicine and make heavy industries like cement more climate-friendly.

New research shows that African forest elephants play a powerful role in fighting climate change by naturally managing forests as they move and feed. By eating fruit from high carbon-storing trees and spreading their seeds, while trampling lower-density vegetation, elephants help forests grow healthier, more diverse, and better at absorbing carbon. Scientists describe them as “gardeners of the forest,” and say their impact highlights how protecting large animals can directly support climate resilience and ecosystem health far beyond Africa.

Enjoying The Hillsberg Report? Share it with friends who might find it valuable!

Haven't signed up for the weekly notification?

Subscribe Now