Quote of the week

“You can’t use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

- Maya Angelou

Edition 47 - November 23, 2025

“You can’t use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

- Maya Angelou

The report that Tim Cook could step down as Apple CEO as soon as next year feels like more than a standard succession story. Apple’s board and senior team are said to be accelerating their plans, with hardware chief John Ternus viewed as the favorite to take over. Cook has led Apple for over fourteen years, through the iPhone super cycle, the Apple Silicon transition, and a steady march of services growth. The real question now is whether the next phase of Apple is about defending the fortress or building something genuinely new.

Set that next to what is happening inside Google. While Apple fine tunes its handover plan, Google is shipping Gemini 3, a clear jump in capability that sits on top of its own TPU infrastructure and the rest of Google’s data and distribution stack. That is not a cautious move, it is a statement that the company intends to compete at the frontier of AI rather than simply integrate it into existing products. At the same time, Sergey Brin has returned to a hands on technical role, reportedly writing code and working directly with teams again. One company is managing a careful transition; the other is acting like it is still in the building phase.

The differences between these two companies are not really about which set of employees are better. It is about how leadership chooses to organize and behave. Apple has become a full bureaucracy that optimizes for predictability, secrecy, and supply chain excellence, while Google has turned its leadership posture back toward direct contact with the work. The result is a very different feel to the pace and ambition of each company.

Founder energy is a special kind of leverage. A founder who still holds significant equity can push through layers of process, force tradeoffs, and personally arbitrate which ideas get resources. That person can sit in a model review in the morning and a product review in the afternoon and make decisions that connect architecture to user experience without a long game of telephone in between. When that kind of influence is pointed at a clear goal, culture bends around it. That is what seems to be happening at Google right now.

The real story is that founder energy is becoming a competitive advantage again. In an AI driven cycle where models, chips, and products are all moving at once, the companies with leaders close to the code will likely out iterate the ones that manage from a distance. Apple is entering a succession moment just as Google is rediscovering its early DNA. If you want to understand who excels over the next decade, it is worth paying less attention to launch event slogans and more attention to who inside these companies has both the authority and the appetite to build.

I was reading a piece on robotaxis and suburbia that argued self driving cars could unlock a new wave of sprawl by making it painless to live farther from everything. You can find it here: Robotaxis and Suburbia. The core idea is simple. Once your car can drive itself, the cost of distance drops and people start to rethink where they live. That idea stuck with me because it intersects directly with a very practical question in my own life.

My wife and I share one car, an old 2016 Hyundai Elantra. It is fully paid off, it still runs well, and it has been incredibly reliable. Even so, I keep circling the idea of getting a new car or leasing one. I want an SUV that feels safer for us, with all the new tech baked in. We would benefit from having two cars instead of one. Four wheel drive would help with the snowy Pennsylvania winters. If I am honest, the most tempting feature might be cooling seats after a gym session.

We have already passed on some attractive offers like zero percent APR and zero percent down. This is not a story about being unable to afford it. We have planned well and could make the numbers work. So why am I still hesitating? Robotaxis. I can see a path where autonomous ride services expand across the United States over the next three to five years, and where by something like seven to ten years from now only a minority of people are still driving themselves.

The transition makes sense on multiple fronts. The economics improve when you remove the human driver. Safety should improve when you remove human error. Quality of life goes up when your commute becomes time you can use for something else. Once the technology scales, it is hard to imagine society not leaning into it. My timelines are not pulled out of thin air. They come from the research I have done and the experts I listen to who spend their time thinking about autonomy.

The harder question is which cars will participate in that future. Tesla looks like a clear leader. There are early signals that some older cars might be retrofitted with new autonomous hardware, although it is not obvious how broad or how durable that path will be. It is hard to imagine every non autonomous vehicle being scrapped, so a car I buy today might be upgradeable and my anxiety might be misplaced. Or the revolution might arrive more slowly than I expect and sticking with my Elantra could be the rational choice. For now I am living in the tension between today’s needs and tomorrow’s autonomous reality, and every time I turn the key I wonder how much longer most of us will be driving at all.

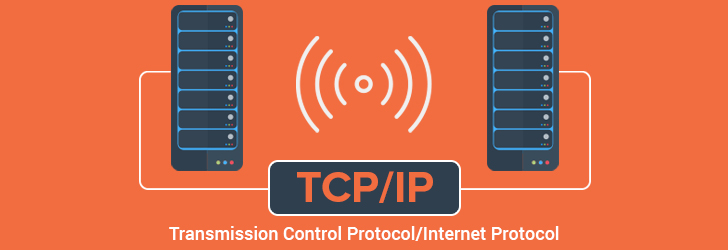

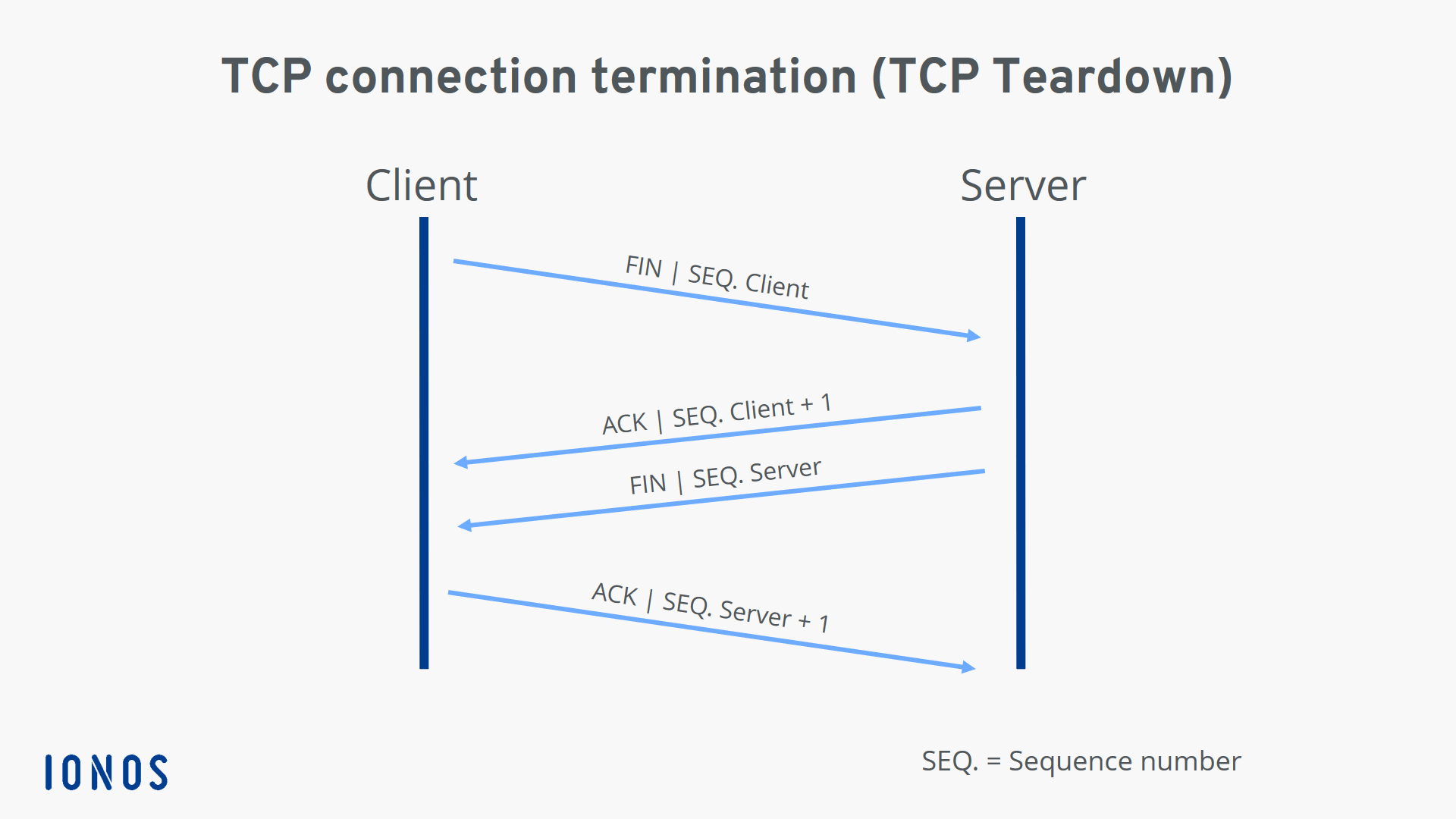

The internet feels smooth and reliable, but underneath it is a messy system where packets can be delayed, lost, or delivered out of order. Transmission Control Protocol, or TCP, is the part of the network stack that hides most of that chaos so apps can just send and receive data. In a recent deep dive into TCP internals, Moncef Abboud walks through how the protocol really works under the hood in practice, not just in theory in his article.

One way to understand TCP is to imagine sending a multi-page letter through an unreliable postal system. Pages can arrive late or out of order and some might not arrive at all. TCP tracks each piece of data with sequence numbers, confirms what arrived with acknowledgments, and requests that missing pieces be sent again. It also controls how fast the sender transmits so the receiver is not overwhelmed and it slows down when the network looks congested. Together these behaviors turn a noisy, imperfect network into something that feels like a clean stream of information.

What makes TCP impressive is how well this design has held up over time. Even as the internet has grown faster and more complex, the basic problems of loss, delay, and reordering have not gone away. TCP smooths them out so loading a webpage or streaming a video feels simple. It gives you the illusion of a perfect connection on top of an imperfect world, and that illusion is one of the key reasons the modern internet could scale to billions of devices.

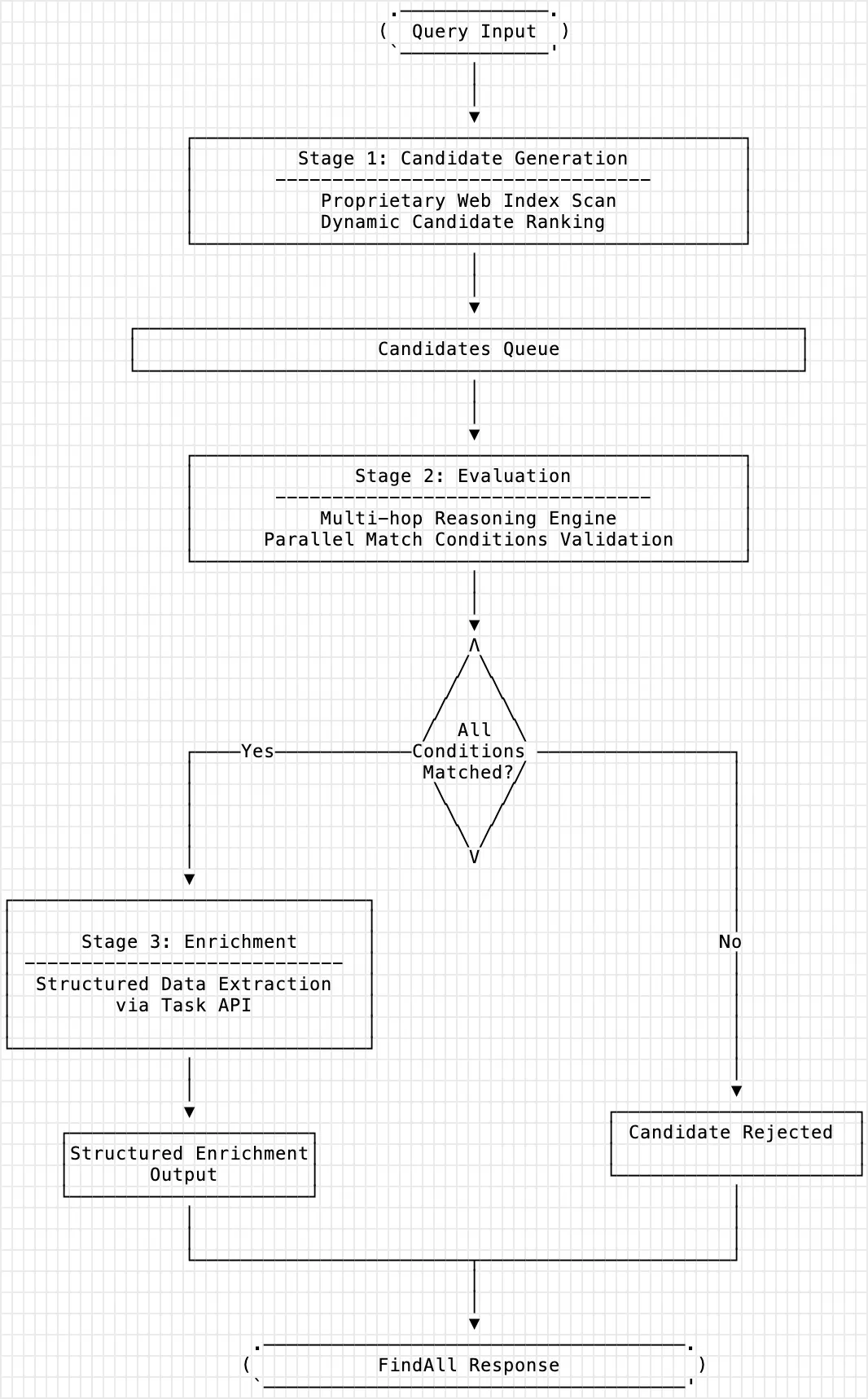

I saw Parallel’s FindAll API on X the other day and it immediately caught my eye. FindAll is an API that turns a plain language query into a structured dataset built from the web. Instead of returning a list of links, it returns entities that match your description plus the facts you care about. In their words, it lets you turn the web into your own structured dataset, which is a useful mental shift. Search has always treated the web as pages to browse. FindAll treats it as a giant database you can query.

What can you do with that in practice. Think of a sales ops person who writes “Find all dental practices in Ohio with at least 4 star Google reviews and more than five employees.” Or a climate investor who asks for “climate tech startups with active pilots with Fortune 500 companies, pre Series A, focused on carbon capture or storage.” The API returns a list of entities matching those constraints plus attributes like location, headcount, funding stage and links to sources. You can use it to assemble prospect lists, merger and acquisition target maps, market landscapes, or watchlists for compliance. Instead of buying a fixed dataset or wiring up your own scraping pipeline, you describe the dataset and let the API build it for you.

Under the hood, FindAll follows a simple pipeline. First it generates candidates from their web index, which is tuned for entities like companies, people or locations. Then it evaluates each candidate against your match conditions using a mix of retrieval and model reasoning. That step filters out entities that do not truly satisfy the query. Finally it enriches the remaining entities by calling their task style API to pull structured fields for each one. The output is not just a name and a URL but a mini profile with attributes, reasoning about why it matched, links to supporting pages and a confidence score. The important thing is that provenance comes built in so you can trace any fact back to the web.

Parallel also shipped a second piece that pairs nicely with this. In a thread that I read through on Thread Reader, they introduced the Extract API, which takes a URL and returns clean markdown that is ready for an LLM or any downstream tool. You can ask it for compressed excerpts that focus on a specific objective or for full content when you need everything. That means you can point it at JavaScript heavy product pages, blog posts, documentation sites or even multi page PDFs and still get usable text back. The examples range from pulling full API documentation and code snippets, to extracting methods and results tables from research papers, to lifting the risk factors section from a 10 K filing, to pulling product specs and pricing from ecommerce pages. In other words, it is a general purpose web to markdown converter that understands structure and intent, not just HTML.

Taken together, these two APIs look like early infrastructure for a new wave of web apps. The old pattern was scrape, clean, store, then build your app on top of a database that you maintain. The new pattern is to treat the open web itself as the database, and to use APIs like FindAll and Extract as the query and read layers. A founder could build a SaaS tool where users define their ideal customer profile, then hit FindAll behind the scenes to build the universe of accounts and call Extract to pull deeper facts from each company website and filing. A researcher could spin up a dashboard that tracks new papers in a field and automatically extracts methods and results into a structured view. Compliance teams, competitive intelligence, analyst tools and vertical CRMs all start to look like thin interfaces on top of a programmable web. That is a quietly radical shift, and it is the sort of plumbing that often comes before the big visible products.

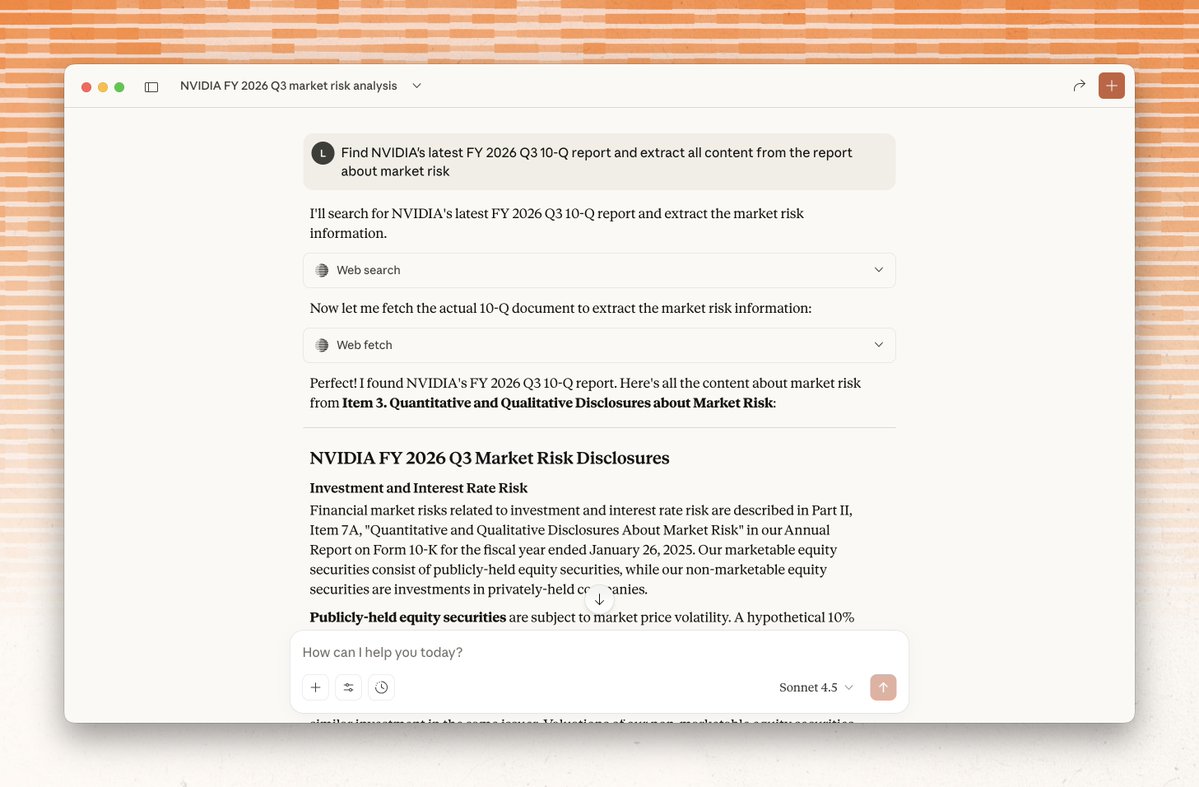

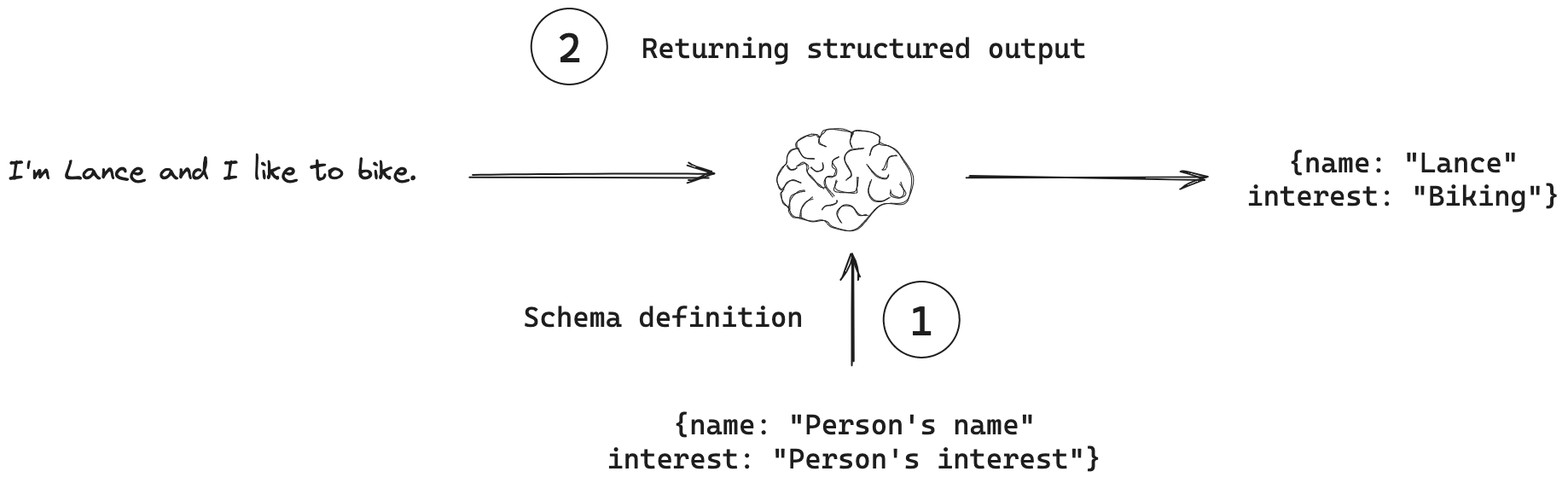

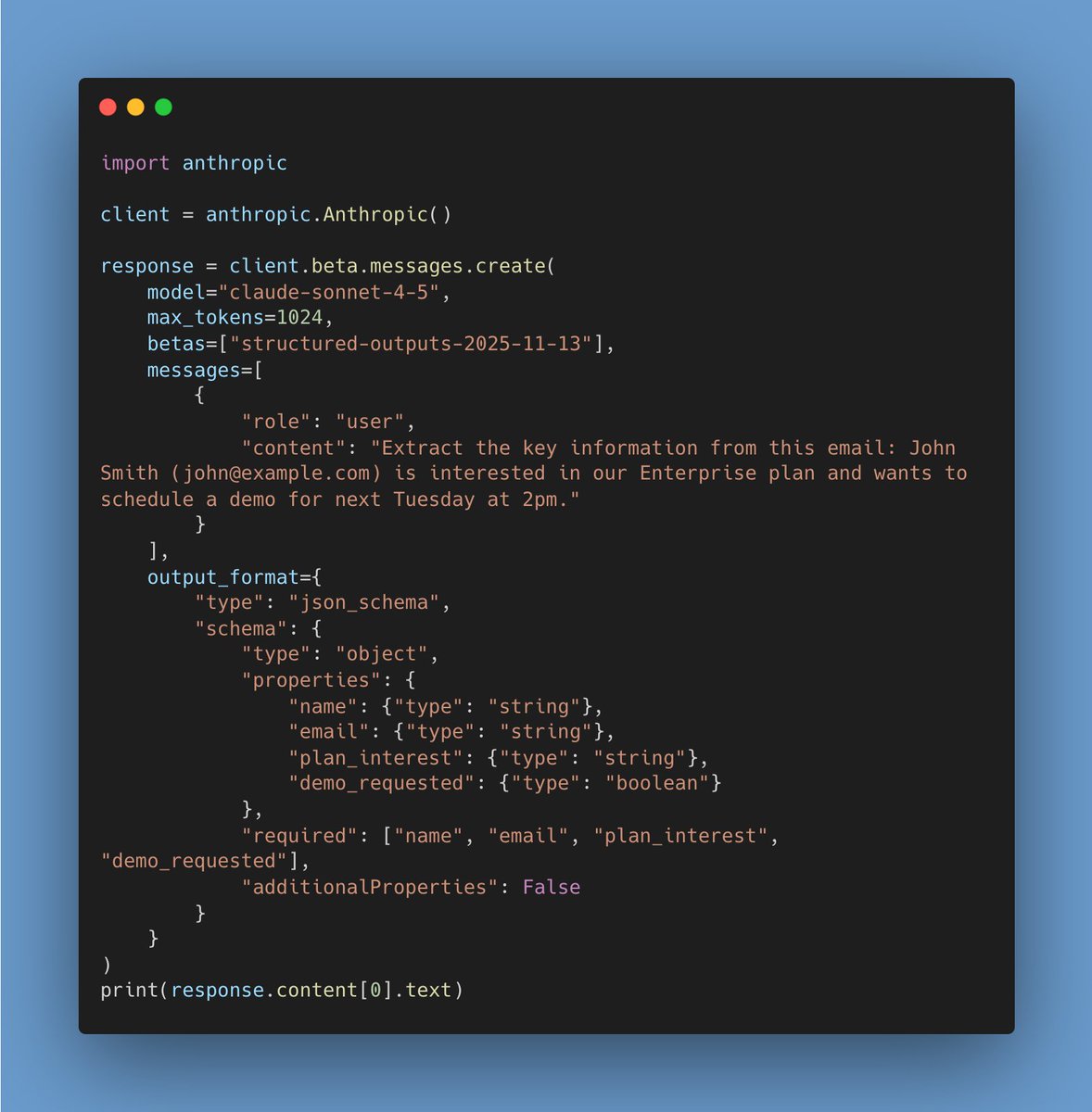

Structured output is quickly becoming the default way to talk to large language models through APIs. OpenAI, Google, Anthropic, and others now let you describe the exact shape of the response you want, often as a JSON schema, and the model is steered to fit that mold. Instead of asking for a paragraph and hoping you can parse it later, you tell the model to return fields like title, summary, and confidence, and you get back a machine readable object that fits into the rest of your system.

Once you have that constraint, a lot of messy glue code disappears. Classification, extraction, routing, and multi step workflows all get easier because downstream services can expect predictable keys and types. You no longer need fragile regexes or string slicing to dig answers out of natural language. The model starts to behave like a typed function: your application can validate, log, and version outputs, then feed them into databases, queues, or dashboards with far less ceremony.

In the early days, everyone faked structured outputs with prompts. You pasted a sample JSON snippet into the prompt, wrote return valid JSON that matches this template, and crossed your fingers. It often worked, but every so often the model would improvise: missing fields, extra commentary, or values in the wrong format. When that happened, the calling code could not parse the response, so you either crashed or built a patchwork of repair scripts. Native structured output support flips that. You define the schema in the API call, the provider uses constrained decoding and validation under the hood, and you only see a parsed object that fits the contract, or a clear error that you can retry.

For evaluation, this changes what you care about. At my company I am in the middle of building evaluation infrastructure, and we are about to adopt Braintrust as our main evaluation and experiment layer. The good news is that Braintrust already understands structured outputs. In its prompt playground you can select structured output and attach a JSON schema so responses are parsed as objects instead of raw text, which maps directly to the structured output features in the OpenAI API. Braintrust exposes metrics such as JSON diff and lets you write scorers that check structure and formatting, including whether an output follows a required JSON schema, so you can treat schema validity as a first class signal, not just a parsing step.

I still expect some sharp edges. Complex nested schemas, cross field constraints, and mixed provider setups may not all be handled cleanly in a point and click UI. The likely pattern is to treat Braintrust as the log and score store, then run schema aware checks in code using its SDK or tools like Autoevals and push those scores back for comparison. If that feels heavy, there are alternatives that lean into structured outputs as well, such as Langfuse, which now lets you enforce JSON schemas in experiments and attach custom scores that track whether an output was valid JSON or matched particular fields. Across these tools, the direction is clear: structured outputs will not only shape how we call models, they will become the backbone of how we test and trust them.

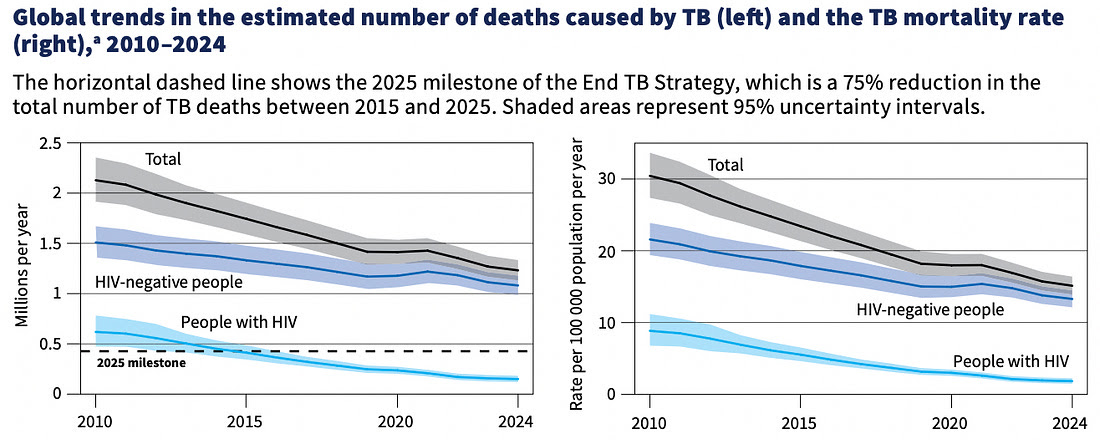

Global TB deaths have fallen by 29% since 2015, with a new WHO report showing mortality down to 1.23 million in 2024, the lowest ever recorded. The African and European regions led with reductions of 46% and 49%, and more than 100 countries have cut TB deaths by at least 20% since 2015. After the setbacks of the pandemic, the world is finally returning to a steady downward trend.

Scientists on both sides of the Atlantic are opening new fronts against cancer. In the United Kingdom, researchers are pushing advances in prevention and ultra-early detection, from the first trials of cancer-stopping vaccines to blood tests that can spot tumours long before scans can. In the United States, progress is centered on precision treatment, with immunotherapies, CAR-T, targeted radiation and engineered viruses giving new hope for cancers that were once untreatable. Taken together, these trends are converging as prevention, early detection and precision therapy begin to overlap, shifting cancer from a likely death sentence toward a manageable condition.

Egypt has eliminated trachoma after more than 3,000 years. It is now the seventh country in the Eastern Mediterranean region and the 27th worldwide to remove the world’s leading infectious cause of blindness as a public health problem. The milestone follows a decade of detailed mapping, ongoing surveillance and a nationwide rollout of the WHO elimination strategy.

Enjoying The Hillsberg Report? Share it with friends who might find it valuable!

Haven't signed up for the weekly notification?

Subscribe Now