Quote of the week

“Do not go where the path may lead, go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.

- Muriel Strode

Edition 36 - September 7, 2025

“Do not go where the path may lead, go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.

- Muriel Strode

Hallucinations are the Achilles’ heel of modern artificial intelligence. For all their dazzling abilities, from drafting essays to writing code to summarizing legal contracts, AI systems still have an unnerving habit of making things up. Sometimes it is minor, like inventing a fake book citation. Other times it is serious, such as misquoting laws, giving inaccurate medical advice, or fabricating financial data. The problem is not just that models get things wrong, but that they deliver these falsehoods with total confidence. For users it becomes difficult to distinguish fact from fiction, which undermines trust in the very tools meant to amplify our intelligence.

In a new post and research paper, OpenAI takes a closer look at why hallucinations persist. Their argument is that it is not just about the models themselves but also about the way they are tested and rewarded. Today’s benchmarks overwhelmingly value accuracy. That sounds good in theory, but it creates an odd incentive. Models learn that it is better to guess than to admit uncertainty. If they guess correctly, they score points. If they say “I don’t know,” they get zero. Over time this system teaches models to bluff, which is exactly what leads to hallucinations. OpenAI argues that evaluation methods need to change. Instead of rewarding blind guesses, tests should give partial credit for appropriate uncertainty and penalize confident wrong answers more heavily.

This is more than talk. OpenAI has already started to emphasize calibration in GPT-5 and its smaller variants. Their system card shows that GPT-5 is more likely to abstain when unsure, which reduces error rates even if it sometimes looks less accurate on traditional scoreboards. This reflects a shift in philosophy. Accuracy at all costs is not the right metric. Reliability, knowing when not to answer, may matter more. Technically this is feasible because models can already quantify uncertainty in their internal probabilities. The challenge is integrating that signal into user-facing behavior without making the model feel hesitant or evasive. Nobody wants a chatbot that responds “I don’t know” to everything.

There are obstacles. The broader AI industry is hooked on leaderboards. Accuracy percentages are easy to rank and market, so companies compete for higher scores rather than better calibration. Changing incentives means changing the scoreboard itself, which requires coordination across research groups, companies, and customers. Calibration is also tricky in practice. A small model can easily admit ignorance when faced with an unfamiliar language, but a bigger one with partial knowledge has to decide how confident is confident enough. Even if models learn to abstain, there is the question of whether users will trust them more or simply grow frustrated when the system refuses to help.

If hallucinations are truly minimized, the implications are huge. Imagine AI systems being deployed in medicine without the looming risk of fabricated studies. Picture lawyers using AI to draft contracts without worrying about phantom case law. Financial analysts could rely on AI driven insights without constantly fact checking every number. Parents could confidently use AI tutors knowing the answers given to their children are correct, or clearly labeled as uncertain when they are not. Eliminating hallucinations could transform AI from a powerful but unreliable assistant into something closer to a trusted partner.

The road is long, and OpenAI admits that hallucinations may never fully disappear. But if the industry takes their proposed shift seriously, rewarding honesty as much as accuracy, then the next leap in AI progress might not come from bigger models or faster chips. It might come from teaching our machines the value of humility.

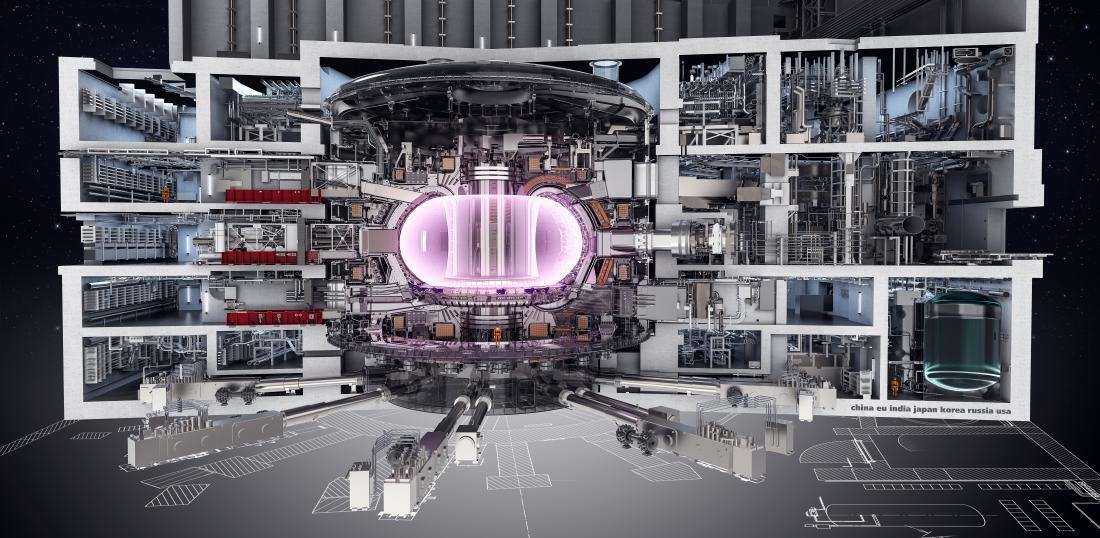

The world’s most ambitious energy experiment is entering a decisive stage in southern France. At the ITER project site, scientists and engineers from 35 nations are building a fusion reactor designed to mimic the power of the sun. If it works, ITER could deliver a future of clean and nearly limitless energy, free from the long-lived waste and risks that come with today’s (older generation) nuclear plants. The stakes are enormous, and the outcome could redefine how humanity powers its civilization.

At the heart of the project is the tokamak, a doughnut-shaped chamber that will heat hydrogen plasma to more than 150 million degrees Celsius. Inside, atoms will fuse together and release energy in quantities far greater than the input required to ignite the reaction. ITER’s target is a tenfold energy gain, a proof of concept that fusion can be scaled to commercial power production. It is not meant to light homes on its own, but it will lay the foundation for reactors that can.

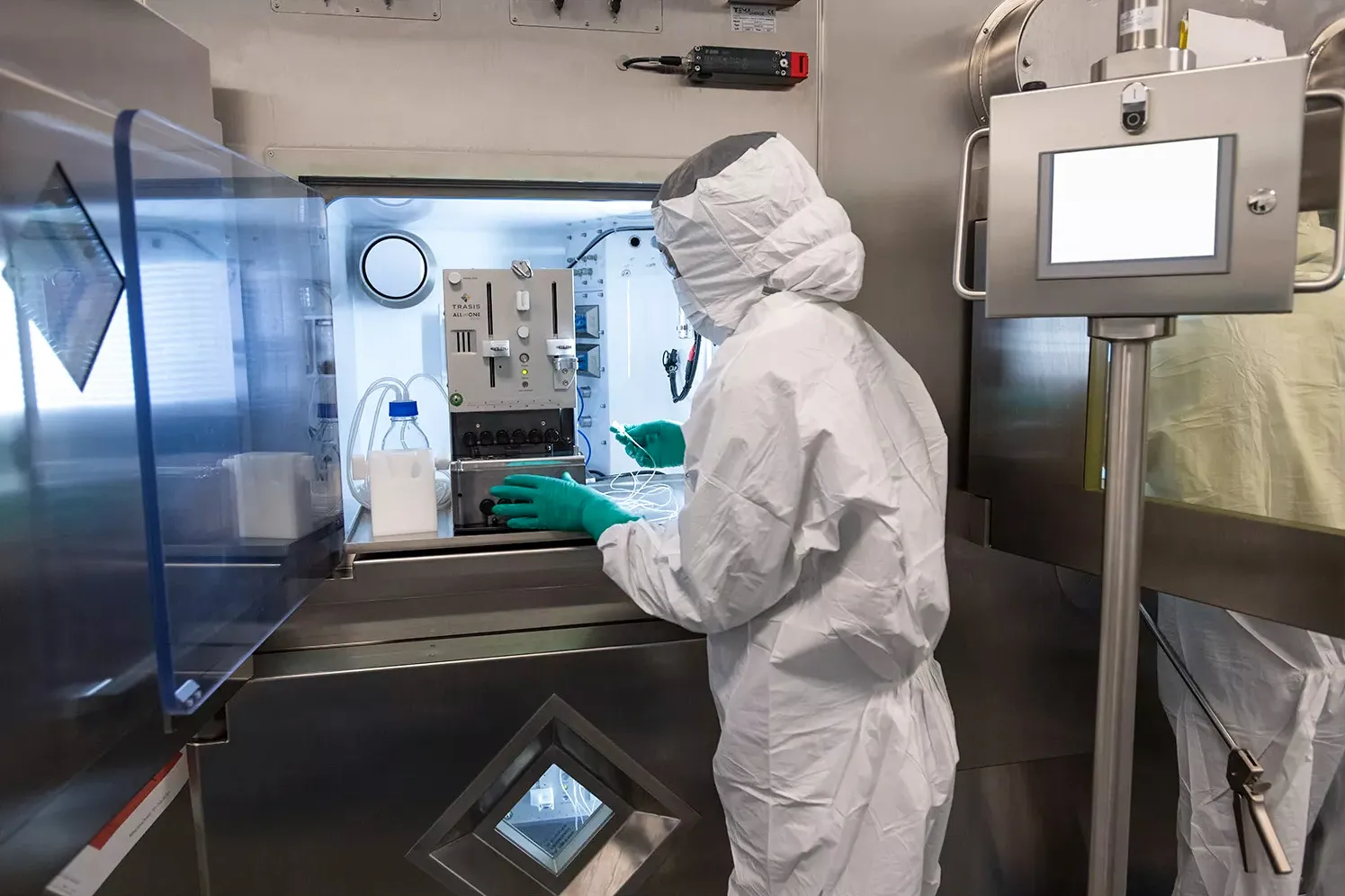

Leading this critical phase is Westinghouse Electric Company, which recently secured a contract worth 168 million euros to assemble ITER’s vacuum vessel. The structure is made of nine steel sectors, each weighing 400 tons, that must be welded together with near-perfect precision. Westinghouse brings more than a decade of experience with ITER, along with a track record in nuclear technology that makes it one of the few companies capable of managing such a task. The precision demanded by this stage has been compared to building a three-dimensional puzzle on an industrial scale.

Westinghouse’s involvement is the latest chapter in a long story. Founded by George Westinghouse in 1886, the company was an early pioneer of alternating current and a key rival to Thomas Edison in the race to electrify the United States. Over the decades it expanded into nuclear power, supplying reactors and systems worldwide. The company has survived financial collapses, reorganizations, and changes in ownership, yet it has managed to maintain its identity as a leader in the energy sector. That resilience has now placed it at the forefront of the most daring energy project of the century.

For ITER and for Westinghouse, the next steps are daunting but historic. The final assembly will take years, and the first full-scale fusion experiments are not expected until the 2030s. But every piece that comes together in Cadarache brings the world closer to a breakthrough that has eluded scientists for generations. Fusion may still be decades from powering cities, but with Westinghouse guiding the assembly of the core, humanity is closer than ever to capturing the energy of the stars.

I am reading a book called Life 3.0 by Max Tegmark. I wanted to share this excerpt because I found it both timely and fascinating.

Yet another interesting legal controversy involves granting rights to machines. If self-driving cars cut the 32,000 annual U.S. traffic fatalities in half, perhaps carmakers won’t get 16,000 thank-you notes, but 16,000 lawsuits. So if a self-driving car causes an accident, who should be liable—its occupants, its owner or its manufacturer? Legal scholar David Vladeck has proposed a fourth answer: the car itself! Specifically, he proposes that self-driving cars be allowed (and required) to hold car insurance. This way, models with a sterling safety record will qualify for premiums that are very low, probably lower than what’s available to human drivers, while poorly designed models from sloppy manufacturers will only qualify for insurance policies that make them prohibitively expensive to own.

But if machines such as cars are allowed to hold insurance policies, should they also be able to own money and property? If so, there’s nothing legally stopping smart computers from making money on the stock market and using it to buy online services. Once a computer starts paying humans to work for it, it can accomplish anything that humans can do. If AI systems eventually get better than humans at investing (which they already are in some domains), this could lead to a situation where most of our economy is owned and controlled by machines. Is this what we want? If it sounds far-off, consider that most of our economy is already owned by another form of non-human entity: corporations, which are often more powerful than any one person in them and can to some extent take on life of their own.

I’ve long been fascinated by the intricate global web of insurance and reinsurance. To understand how this system works today, it helps to look at where it began. The very first insurance-like arrangements already reveal the conditions that make coverage possible. Around 1750 BCE in Babylon, merchants borrowing money for shipments had a simple but powerful clause: if goods were lost to storms, theft, or piracy, the debt was forgiven. Fast forward to early modern Europe, and you see fire insurance emerging after the Great Fire of London in 1666, protecting cities from ruinous urban blazes, and life insurance taking shape in the 1700s to safeguard families against premature death.

What makes something insurable is not random. Over time, insurers and regulators formalized a standard set of conditions known as the Characteristics of an Insurable Risk. These are the principles that separate manageable risks from those that would overwhelm the system:

When the internet was carved up in the 1980s, Anguilla was handed the domain ending .ai. It seemed trivial at the time, but four decades later those two letters are a digital goldmine. With the explosion of artificial intelligence, entrepreneurs and tech companies are snapping up .ai domains as fast as they can. Some names sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars, like you.ai for $700,000, while standard registrations run around $150 to $200.

For the island of just 16,000 people, the payoff has been dramatic. Last year the government earned nearly $40 million from domain sales, almost a quarter of its revenue. That income is helping diversify an economy that normally relies on tourism and is vulnerable to hurricanes. Unlike Tuvalu, which undersold its .tv address for a fixed fee, Anguilla struck a revenue sharing deal that lets its earnings grow with demand.

Officials now see the .ai windfall as a way to fund new infrastructure, health care, and even a new airport. As the number of domains races toward one million, Anguilla’s unlikely piece of digital luck has become a cornerstone of its financial future.

Global rice prices are tumbling as the world heads toward its largest harvest in nearly 20 years. Favorable weather and decades of farming advances are driving expected production for 2025–26 to about 523 million tonnes. That bumper crop is set to push prices down to their lowest in 8 years, easing food costs for billions worldwide.

Africa is finally emerging from a decade of debt crises. For the first time in ten years, no country on the continent is officially in distress, with Mozambique the last to exit as its borrowing costs fell. Debt levels remain heavy and continue to slow growth, but pressures are easing with IMF-led restructurings, lower inflation, and a revival of investor interest.

After more than a century of industrial damage, the Chicago River is coming back to life. Fish are returning, recreation is growing, and pollution is falling. Massive investments in sewage treatment and stormwater systems have turned what was once an open sewer into a recovering urban waterway.

Two breakthroughs are transforming cancer research. Novartis’s radioligand therapy, which delivers radioactive isotopes directly into tumors, has wiped out metastatic cancers in trial patients—an unprecedented outcome. Meanwhile, U.S. scientists discovered that blocking the immune protein IL-23 makes HPV vaccines effective against existing tumors, opening the door to therapeutic vaccines.

Enjoying The Hillsberg Report? Share it with friends who might find it valuable!

Haven't signed up for the weekly notification?

Subscribe Now